The Vintage Voyageur

The Modern Dandy's Podcast - Natty Adams Episode

Dapper Villains Podcast - Natty Adams Episode

Inside Hook - Patterned Shirts

Reclaiming Brummell

I know I’m a little bit late to this, but about a week ago the writer Alexandra Rowland wrote a long twitter thread criticizing Beau Brummell. This thread was then adapted into an article for Esquire. The author raised some good points but I also think they missed some important aspects of Brummell’s legacy. Seeing as I’m a Brummell buff and I even sell the beautiful Fratelli Mocchia di Coggiola Brummell shirt depicted above in my shop, I wrote this response as a letter to the editor at Esquire.com. They never responded, so I’m publishing it here on my blog. I hope it adds a different and valuable perspective to the discussion.

Dear Editor,

My name is Nathaniel Adams and I’m the co-author - with the photographer Rose Callahan - of “I am Dandy: The Return of the Elegant Gentleman,” and “We Are Dandy: The Elegant Gentleman Around the World.” I don’t think it’s unfair of me to say that I’m one of the world’s experts on the subject of dandies and dandyism. I gave a TEDx talk on fashion and free speech a few years ago and I’ll be speaking at Disneyland in a few weeks on the subject of Style and Empowerment.

It is in the spirit of this last topic that I would like to respectfully respond to Alexandra Rowland’s vigorous takedown of Beau Brummell. I’m afraid that their characterization of him as a stuffy uptight conservative misses the point of why he matters and why his legacy can be seen as a radical and pro-experimental one, rather than the opposite, as they argue. Personally I’m a relatively flamboyant dresser who embraces lots of color and the other things Rowland claims Brummell tore out from the masculine sartorial vocabulary, and I - and many of the hundreds of dandies from all over the world from Tokyo to Johannesburg whom I’ve interviewed (who range from conservative to flamboyant in their personal tastes but all bespeak elegance and beauty in male style,) - see Brummell as a kind of mascot of sartorial liberation rather than a historical gatekeeper of conformity.

Beau Brummell was indeed a jackass by many standards - he was rude, he took great pleasure in cutting people down, he liked to start rumors about things like him polishing his boots with champagne, and he did set the style of his time and was fanatical in his fastidiousness. Whether you see value or vice in these things is a matter of degree and opinion. The dandies of the Regency were admittedly pretty frat-boyish - they spent most of their time gorging themselves on food and wine, gambling away fortunes, going to prizefights, and visiting prostitutes. But to say that men were expressing themselves more through their style before Beau Brummell is exactly backward. Before Brummell, men were mainly expressing wealth and social status through their jewels and fine threads, beautiful and glittering though they may have been. After Brummell the clothes, their cut, and their arrangement became the actual medium of expression, rather than a mere billboard for affluence. Brummell turned dressing itself into an art and intellectual exercise in its own right. And since then Brummell’s radical use of masculine elegance as a kind of power has been employed to great effect by all kinds of men - including and especially marginalized ones - from Oscar Wilde and Jack Johnson in the last two centuries to the Sapeurs of Brazzaville and the Mr. Erbil club of Iraqi Kurdistan today.

Rowland has most of their facts on Brummell straight - and I agree with their assessment that he was probably a big old jerk - but I think they've missed what the actual legacy of Brummell as an icon is and what his name and gift for innovation (even if it was an innovation of subtlety,) means to men like me and many others around the world who strive to proudly carry on the tradition of dandyism as a radical sartorial choice.

I'm glad to see so many different people debating the significance of someone like Brummell and the meaning of dandyism, but it can be tempting to make a 200 year-old historical figure into a caricature or easy target for blame because of his unlikeable personality or without reckoning with the broader implications of the legacy of his life's work. I remain hopeful that people like me and Rowland who clearly share a belief in and love of sartorial self-expression can continue to have meaningful discussions on who deserves what place in the historical pantheon of fashion while simultaneously uniting agains the Athlesiure Class that threatens to drown us all in drab spandex.

Ever yours,

Nathaniel “Natty” Adams

Other Men Need Help Podcast

Dear Readers,

I recently had the great pleasure of being interviewed by Mark Pagan for an episode of the “Other Men Need Help” podcast entitled “Fancy Pants.” You can find the episode here:

National Arts Club Podcast featuring me and Rose

The National Arts Club in New York City and the chair of its fashion committee, David Zyla, have been incredibly supportive of my and Rose’s projects since even before our first book, “I Am Dandy” was published. Since then, and through the “From Tip to Toe” book I contributed to as well as the publication of our second book, “We Are Dandy,” the National Arts Club has invited us to speak on several panels, displayed Rose’s photographs in their galleries, and always made us feel welcome. Now, they’ve done us the distinct honor of having us be guests on one of the first episodes of their brand new podcast series. Listen at the link below - I hope you enjoy it!

National Arts Club Podcast - Episode 2 - Rose Callahan and Natty Adams

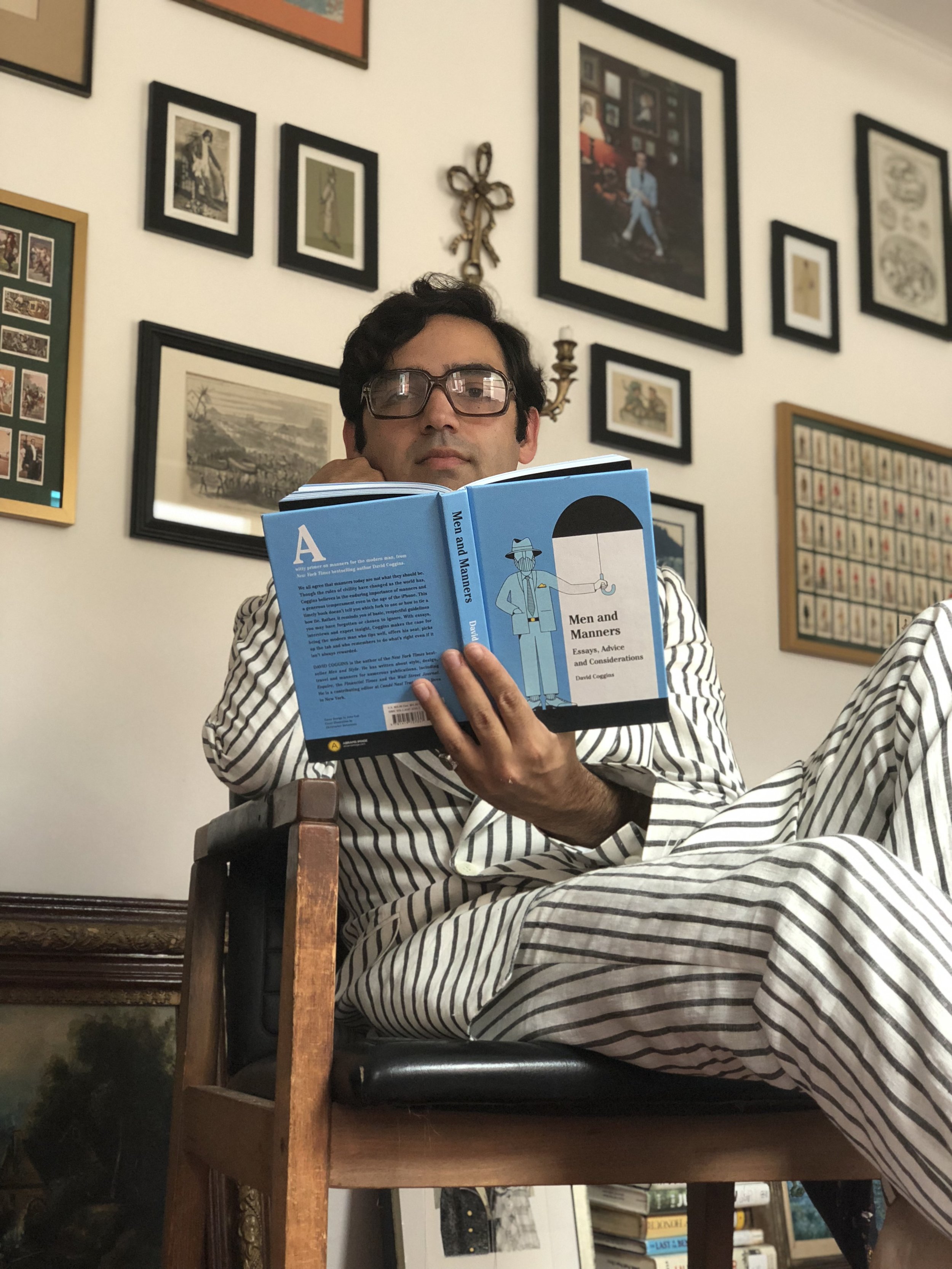

To The Manners Born

In a year in which I've published little of great consequence, it's a particular delight to have been invited by my friend David Coggins to contribute a few thoughts to his excellent book Men and Manners, (Abrams, 2018,) the follow up to his New York Times best-selling Men and Style (Abrams, 2016.) I was as shocked as you that someone would want my opinion on manners of all things, but when I learned that part of the job involved me grousing about things that annoyed me, I felt safely on my home turf again. The book is truly wonderful to read: witty, warm, and with a generosity of spirit befitting the subject. It is a book that treads lightly, never taking itself too seriously, occasionally self-deprecating, and above all patient. In fact, if I were to distill all of the lessons of this book down to one virtue, it would be patience. A few oblique references are made at the beginning of the book to the tense and angry political climate post-2016, and a subtext that occurred to me while throughout was: "above all else, keep your cool" - Coggins counsels (indeed channels,) the almost zen-like magnanimity of our last president.

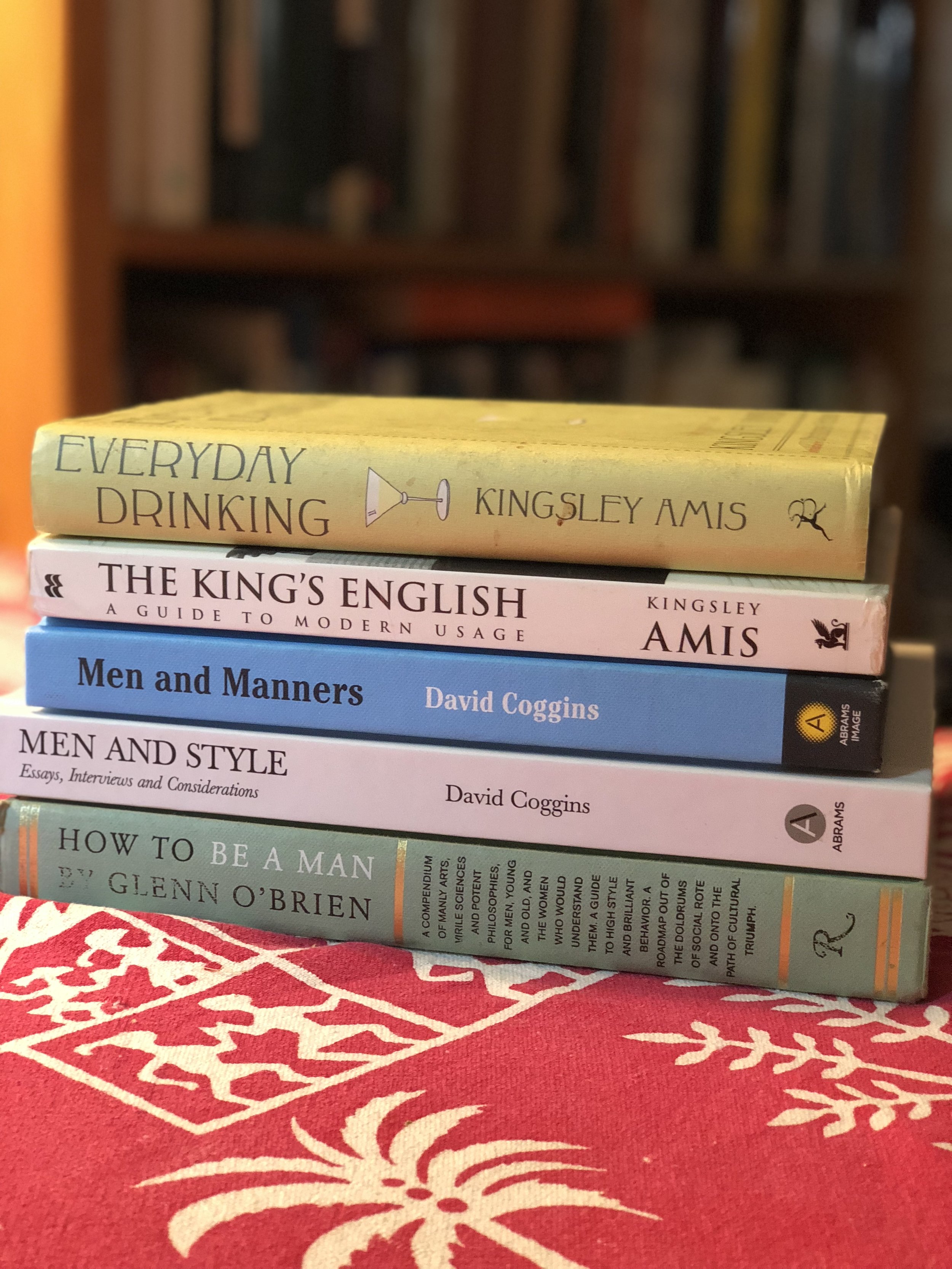

Books of advice are tricky things, and notoriously difficult to shelve at a bookstore (this canny and semi-ironical gem certainly doesn't seem at home in the high-stakes con-artist-filled self-help section.) My two favorite advice books are both by the same author on different subjects: Kingsley Amis's Everyday Drinking (the compiled version with the Christopher Hitchens introduction,) and The Kings' English, Amis's hilarious and savage defense of proper English usage. This book is similar in style to those (though less obviously curmudgeonly,) and even name-checks the first volume mentioned. Aside from a taste for nice clothes, good booze, and Kingsley Amis, Coggins and I also share two mentor/friends in writers Gay Talese and the late Glenn O'Brien. In fact, both of Coggins's books are most like O'Brien's How to be a Man in feeling and intent. Coggins and I also both have close relationships with our fathers, and I was delighted to share a piece of my father's wisdom for the book, and then give him a copy of it for Father's day. Unfortunately, I forgot to include my dad's Bartleby-like motto "you don't have to do anything."

Adams, Coggins, Callahan

That the book is such a delight to read is - apart from its excellent style - due to Coggins's easy flexibility as a guide through the pitfalls of modern living; he is confident in his opinions without any pretense of infallibility, unafraid to tell you what he prefers, but - despite the magnificent beard - reluctant to cast himself as a Moses of etiquette. There are a few particularly excellent rules and tips laid down here and there that Coggins insists you shouldn't compromise on and that double as affirmations of the author's good taste. He says "if something will fit when you lose weight then it doesn't fit." This is what I've always referred to disparagingly in the bespoke business as "aspirational sizing," and it is when a man appears most pathetic to his tailor. Coggins has a nearly perfect Martini preference - very cold gin, don't be afraid of the vermouth, stirred, served with a lemon peel twist - that I would only tweak by swapping the twist for a cocktail onion, thereby turning it into a potently bittersweet Gibson. Coggins also recommends the Giotto frescos in Santa Croce, at which point in reading I nearly jumped for joy at the discovery that I wasn't the only person at Pitti Uomo spending quality time off-campus, as it were. Perhaps Coggins's greatest advice is "nobody is your 'bro.'"

The Pentateuch

The closest thing I have to a criticism of the book is that it knows its audience too well, and plays with them very nicely indeed (probably a good and natural thing for a book about manners.) There is no direct discussion about how a good-mannered person deals with people with truly appalling manners, for example. The recommendations are also often New York-centric - Manhattan, specifically - which is something I don't think I would have even noticed until I moved away from the city - so blinkered are even the best-travelled New York cosmopolitans to the possibility of a serious life elsewhere. A section on travel assumes that journeys will be undertaken via airplane and counsels the manners-minded traveller to find ways to make the best of it - my hopes for a full-throated endorsement of a return to rail travel until air travel becomes less of a hellish ordeal went unsatisfied, but that's a personal problem, and Coggins was certainly wise to write for the flying majority. Coggins also nimbly avoids several contemporary cultural minefields (and who can blame him?) by mainly ignoring them: there is a sort of unspoken understanding, gleaned from the various mentions of relationships with women that the man in the title is probably a straight man, and not only that but that he is an educated, urbane, and sophisticated man of some means who travels internationally, stays at hotels, eats at restaurants often, and goes to parties where wine will be drunk. One is somewhat depressed by the almost certain knowledge that the brazen philistines of the world - the ones who have lots of 'bros,' - are exactly the least likely to read a book about things like tipping and grooming and not cutting people off in traffic or spitting on the floor or sending unasked-for anatomical photos to ladies. I often wondered while reading it what the 13 year-old boys I mentor in East Baltimore public schools would make of some of the advice: hold the door for people, check. Don't text during dinner, got it. But own your own tuxedo and hang art on your walls? Is that perhaps too bourgeois and patronizing a concern? The exclusive domain of we privileged and patrician few? Or is it part of a worthy, cultured life for men of any class, color, and creed to aspire to? I may have to bring the book in and ask the kids what they think.

Where the book truly excels is in its treatment of distinctly contemporary social phenomenon for which mores and standards are still evolving: texting, social media posting, online dating. The advice it gives for these is brilliant, always thoughtful, based on principles of fair play, and - most importantly - never arbitrary. The book is also sensitive to and aware of many less-noted social subtleties - Coggins is nothing if not an expert observer of human interaction. The section on how to break up with someone well would have been a blessing to a (not-that-much-)younger me. I was glad to see that my father's advice about knowing when to quit the field and keep the peace in an argument is echoed and elaborated upon in one of Coggins's own sections, which reminded me of one of my favorite song titles: "Why Are You Being So Reasonable Now?" by the Wedding Present. I'm not sure what Coggins is working on next - could he possibly have more sage advice to give? Whatever it is it is sure to be a pleasure to read and a treat for those of us who idly aspire to sophistication.

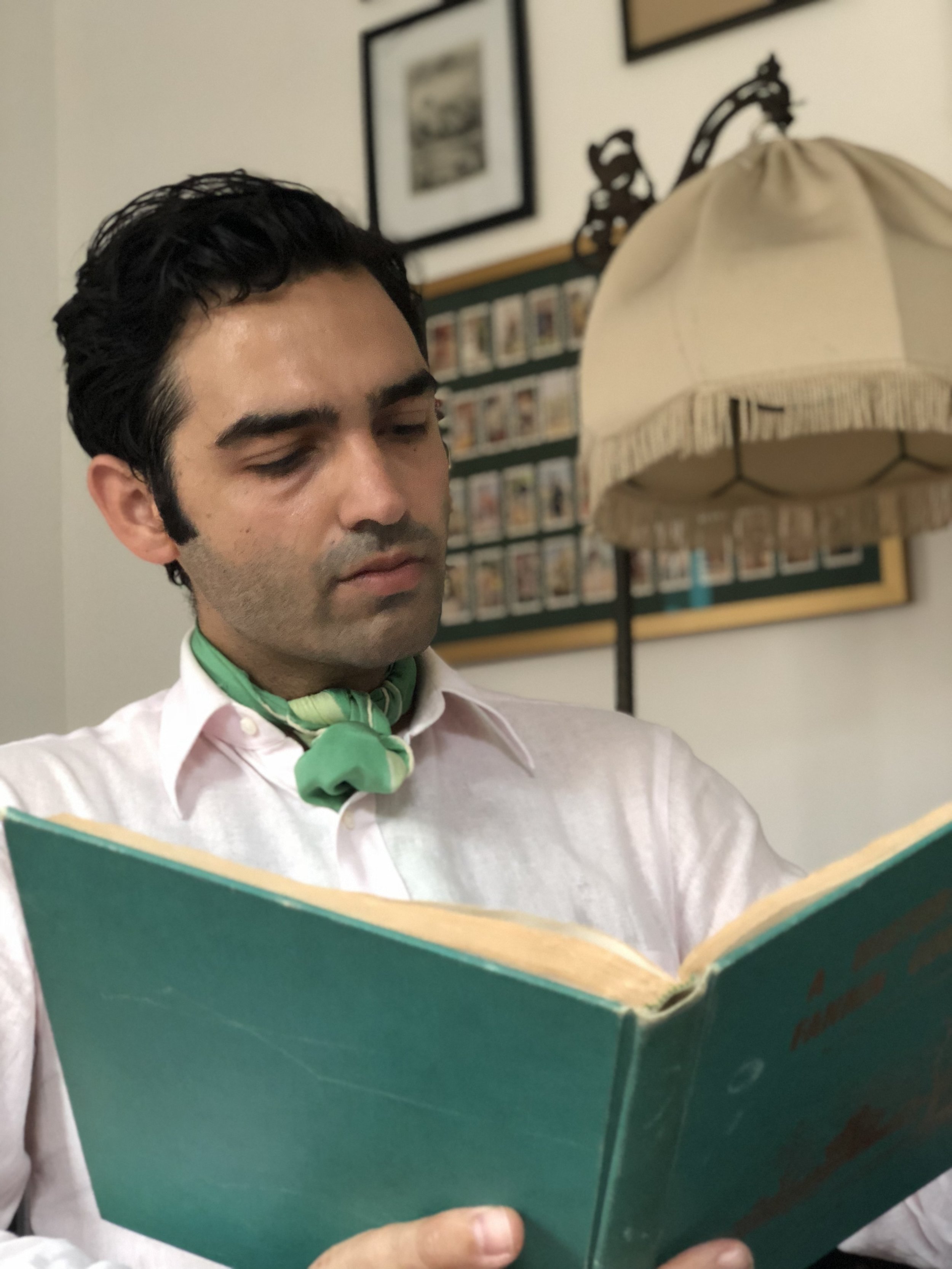

Neck Scarves

The author pining for a shave.

People sometimes ask me what I wear at home, on the days when I don’t go out. It’s true that sometimes I’ll wear a full suit and tie, even if nobody is going to see me all day - there is something mind-focusing about being dressed-up for work. An outfit can give purpose to a day (consequently, I would think exercise best done privately in a nude or semi-nude state, so the mind can focus on the disaster you’re trying to remodel - not that I exercise, of course.)

Mughal print scarf.

But in the hot summer months (when it’s not sweltering and I reach for my kurta,) I have something approaching a uniform: white linen or cotton trousers, a slightly looser-than-usual linen shirt in various colors, and a silk neck scarf. To be clear, this is not an ascot - it’s a less formal thing. I fold it into a triangle, then refold it into a strip, wrap it around my throat, and knot it twice then tuck the ends in. I might fuss with the knots a bit to make sure the right bit of color and pattern comes out.

Coordinating book and scarf and underpants (not pictured.)

Rue de la Paix, 1830

The advantages of a neck scarf are manifold: in pure material and aesthetic terms, silk has a lovely textural contrast to linen. Not having to button your top button or encumber your throat with a tie or bow tie is a blessing in the summer, and best of all the scarf does extra duty absorbing sweat from your neck and providing a barrier between gland and collar.

"What's that? Yes, your finest Diet Sprite."

Almost all of my scarves are vintage, although Hermes, Paul Smith, Drakes, and the Turkish brand Rumisu makes some of the most beautiful scarves around today. And one of the best things about neck scarves is that they’re unimpeachably unisex. Not only does this mean you get an excuse to carouse the women’s department, but it also means you can swap and share them with your partner. It’s the only part of my domestic wardrobe that’s communal (unless you count the leather chaps - but that’s a different matter…)

Mode de Paris, 1866

But the nicest thing about a good scarf are the wonderful prints. It’s a bigger canvas than a tie or a pocket square, and the prints are engineered more often than with those other media. Yes, some scarves are just a repeating pattern, but the better ones are self-contained artworks, and the best even tell a story - perhaps Moby Dick.

"Shredding" on a sweet "axe"

Cam Newton Rolling Stone Article

I wrote this little article about football player Cam Newton's style for Rolling Stone:

We Are Dandy is here!

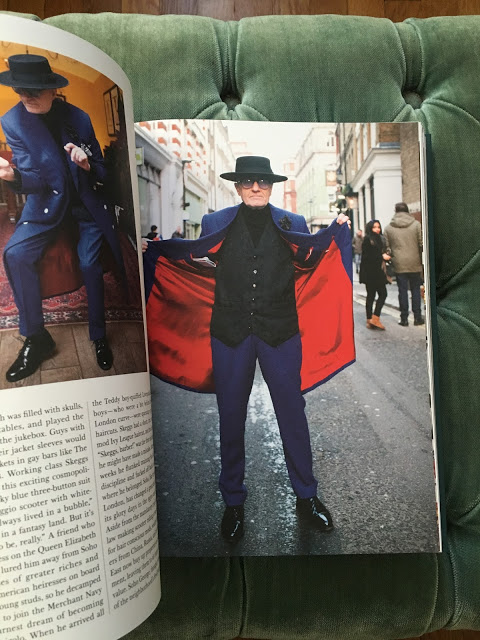

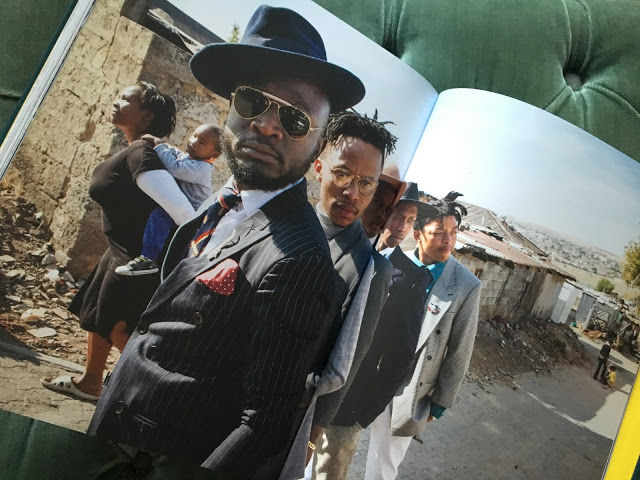

The moment is finally upon us to celebrate “We Are Dandy,” our second survey on international dandyism, this time adding two continents and ten countries to this mighty project. As the world seems increasingly fractious and unmoored, eminent photographer Rose Callahan and I are pleased to report that dandyism not only perseveres but does indeed flourish, even in unlikely and infertile soils.

We spent several months canvassing North America, Europe, Japan, and South Africa for elegant gentlemen, and found ourselves saddled with a surfeit of rakish toffs and sporty knaves all eager to preen and proclaim for our camera and pen. We also somehow managed to convince elegant icon and legendary smokeshow Dita von Teese to write the book’s preface.

I’ll take this opportunity to share a couple of my favorites with you, but I urge you to purchase the book when it goes on sale in the US very soon, ideally from our publisher Gestalten or at your local bookstore. (Although you could also have some company send it to your door via flying robot, I hear.)

Ever yours,

Nathaniel “Natty” Adams