I know I’m a little bit late to this, but about a week ago the writer Alexandra Rowland wrote a long twitter thread criticizing Beau Brummell. This thread was then adapted into an article for Esquire. The author raised some good points but I also think they missed some important aspects of Brummell’s legacy. Seeing as I’m a Brummell buff and I even sell the beautiful Fratelli Mocchia di Coggiola Brummell shirt depicted above in my shop, I wrote this response as a letter to the editor at Esquire.com. They never responded, so I’m publishing it here on my blog. I hope it adds a different and valuable perspective to the discussion.

Dear Editor,

My name is Nathaniel Adams and I’m the co-author - with the photographer Rose Callahan - of “I am Dandy: The Return of the Elegant Gentleman,” and “We Are Dandy: The Elegant Gentleman Around the World.” I don’t think it’s unfair of me to say that I’m one of the world’s experts on the subject of dandies and dandyism. I gave a TEDx talk on fashion and free speech a few years ago and I’ll be speaking at Disneyland in a few weeks on the subject of Style and Empowerment.

It is in the spirit of this last topic that I would like to respectfully respond to Alexandra Rowland’s vigorous takedown of Beau Brummell. I’m afraid that their characterization of him as a stuffy uptight conservative misses the point of why he matters and why his legacy can be seen as a radical and pro-experimental one, rather than the opposite, as they argue. Personally I’m a relatively flamboyant dresser who embraces lots of color and the other things Rowland claims Brummell tore out from the masculine sartorial vocabulary, and I - and many of the hundreds of dandies from all over the world from Tokyo to Johannesburg whom I’ve interviewed (who range from conservative to flamboyant in their personal tastes but all bespeak elegance and beauty in male style,) - see Brummell as a kind of mascot of sartorial liberation rather than a historical gatekeeper of conformity.

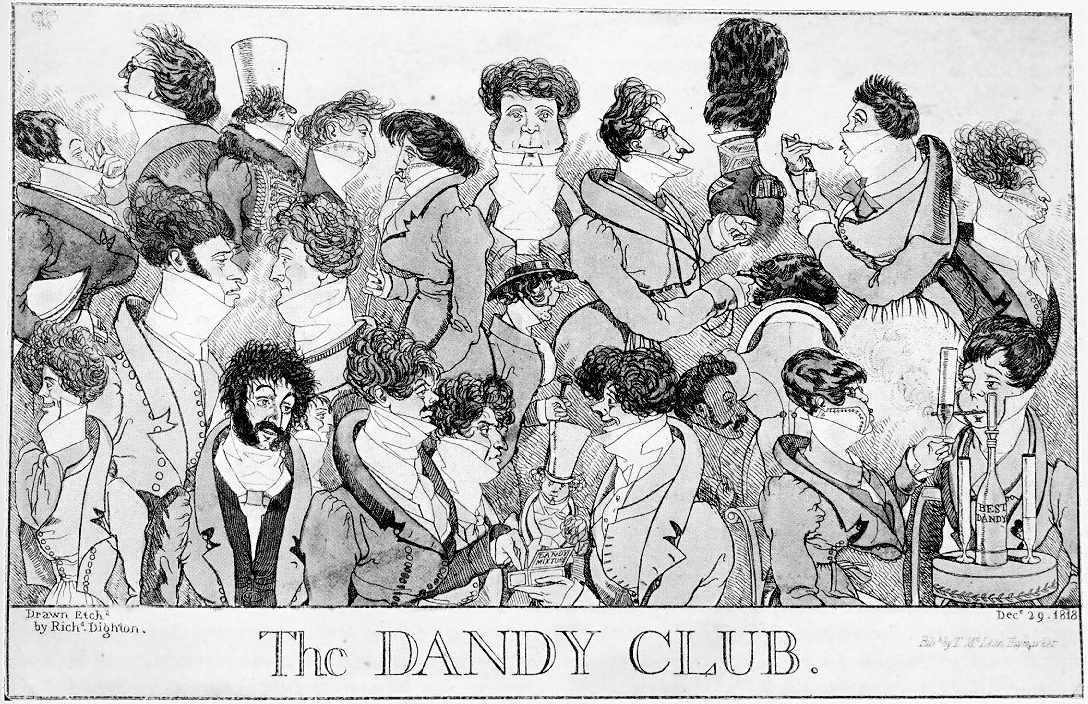

Beau Brummell was indeed a jackass by many standards - he was rude, he took great pleasure in cutting people down, he liked to start rumors about things like him polishing his boots with champagne, and he did set the style of his time and was fanatical in his fastidiousness. Whether you see value or vice in these things is a matter of degree and opinion. The dandies of the Regency were admittedly pretty frat-boyish - they spent most of their time gorging themselves on food and wine, gambling away fortunes, going to prizefights, and visiting prostitutes. But to say that men were expressing themselves more through their style before Beau Brummell is exactly backward. Before Brummell, men were mainly expressing wealth and social status through their jewels and fine threads, beautiful and glittering though they may have been. After Brummell the clothes, their cut, and their arrangement became the actual medium of expression, rather than a mere billboard for affluence. Brummell turned dressing itself into an art and intellectual exercise in its own right. And since then Brummell’s radical use of masculine elegance as a kind of power has been employed to great effect by all kinds of men - including and especially marginalized ones - from Oscar Wilde and Jack Johnson in the last two centuries to the Sapeurs of Brazzaville and the Mr. Erbil club of Iraqi Kurdistan today.

Rowland has most of their facts on Brummell straight - and I agree with their assessment that he was probably a big old jerk - but I think they've missed what the actual legacy of Brummell as an icon is and what his name and gift for innovation (even if it was an innovation of subtlety,) means to men like me and many others around the world who strive to proudly carry on the tradition of dandyism as a radical sartorial choice.

I'm glad to see so many different people debating the significance of someone like Brummell and the meaning of dandyism, but it can be tempting to make a 200 year-old historical figure into a caricature or easy target for blame because of his unlikeable personality or without reckoning with the broader implications of the legacy of his life's work. I remain hopeful that people like me and Rowland who clearly share a belief in and love of sartorial self-expression can continue to have meaningful discussions on who deserves what place in the historical pantheon of fashion while simultaneously uniting agains the Athlesiure Class that threatens to drown us all in drab spandex.

Ever yours,

Nathaniel “Natty” Adams