Jules Barbey D'Aurevilly, the first man to put on paper a critical analysis of dandyism as a cultural phenomenon opens one of the chapters of his work On Dandyism and George Brummell with the frank admission that "Dandysim is almost as difficult a thing to describe as it is to define." This difficulty, at once one of the most intriguing and frustrating things about studying dandyism, has persisted and animated the pens of writers as diverse and accomplished as Baudelaire, Virginia Woolf, Cyril Connolly, and W.H. Auden.

D'Aurevilly, as the title of his essay-cum-biography suggests, took Brummell as his main subject, holding him up as the prime example of a dandy and therefore the embodiment of dandyism as an idea realized. He was not wrong in doing this, although one trap D'Aurevilly never fell into was to assume the fallacy that because Beau Brummell was the ideal dandy all other dandies must therefore follow the style of Beau Brummell. This yawning logical gap neatly avoided by the thoughtful and observant Frenchman has all too often been leapt across (back and forth and back again without the least attempt at original thinking,) by those who would, 200 years after Brummell, declare that dandyism must follow the sartorial principles laid down by that prime mover. There could hardly be anything less dandyish (or more humorless,) than such undeviating idolatry, and one would hope that anyone as spirited and clever as the Beau would have little regard for those who would hold so fast and dearly to what was, at the time, a fiercely independent style.

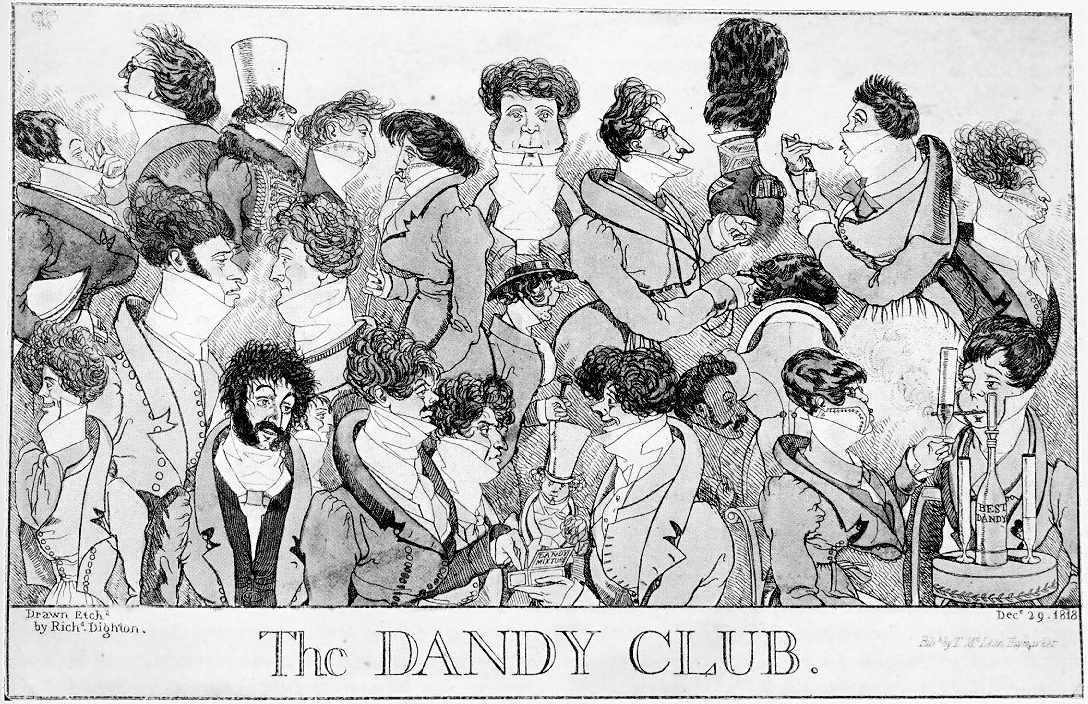

"Dandyism" is not a synonym for Beau Brummell's personal sartorial philosophy or taste. He did not proselytize like some stylish messiah, telling people that he had developed a creed called dandyism and there was a proper way to practice, preach, and worship it. Dandy was a name other people gave to Brummell (as well as plenty of other men at the time whose individual style bore little resemblance to the Beau's elegance-through-simplicity,) and dandyism was a term that was used to refer to a considerably broader set of ideas than Brummell's own notions about the proper way to dress. Brummell is the exemplar of dandyism not because he was objectively the best dressed (although he may well have been,) or because his own personal style was the correct way to dress (although it may well have been,) but because he was the most radical in his style, the most original in his lifestyle and personality, and the most successful in its promotion.

Brummell's oft-quoted remark that "If John Bull turns round to look after you, you are not well dressed: but either too stiff, too tight, or too fashionable," is an excellent summation of his own professed sartorial philosophy (albeit clearly tongue-in-cheek if not a downright lie - Brummell quite obviously did want people to turn to look at him and this was exactly the kind of flippant remark he was fond of making without really meaning,) and it makes reference to one of the key elements of dandyism - that style is more important than fashion. But it is not a definition of dandyism by any means and it is certainly not a dogmatic rule that could stand up on its own 200 years later. If this alone were the definition of dandyism, applied today it would form a loop big enough to accommodate any man in a nicely-cut but determinately not-flashy suit - from James Bond to David Beckham. Not only that, but it would exclude many of the men who came after Brummell and who are now widely considered to be dandies: Count D'Orsay, Baudelaire, Count Montesquiou, Oscar Wilde, Max Beerbohm, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Stephen Tennant, Cecil Beaton, Evander Berry Wall, Lucius Beebe, Bunny Roger, and Tom Wolfe. It seems to me that any definition which would exclude such men for their sometime-flamboyance isn't a definition worth having.

It is true that Brummell's own style was notable for its restraint, simplicity, and anti-flamboyance. It may have been a style which favored subtlety, but this doesn't mean that it was, relatively speaking, a subtle style. It was, in fact, impressive, radical, and aggressive in its simplicity - a stunning reaction to the foppery of his time. Studying Brummell's life, there's every reason to suspect that if he had arrived at a time when the fashion was to dress in a subdued or restrained manner he would have pursued a bolder aesthetic in his own dress.

Defining what dandyism is is a much greater task - one which I hope to achieve in my book. To be sure, dandyism is about dressing well and pursuing a life of elegance, wit, and originality. But one thing it certainly isn't is an unwavering allegiance to Brummell's (or Wilde's, or Loos', or Horsely's) personal ideas about clothing. Dandyism is a far too great subject to be reduced to one man's thoughts about dress. Rather, it is partly a way of thinking about dress - or, more specifically, the belief that dress is something which should be carefully thought about, with beauty, elegance, and originality as paramount considerations. And one should never forget that dress is only one criteria of dandyism and that a monkey in a suit - or David Beckham - will never truly be a dandy.

Despite all my kvetching about arguments from two century-old authority I'll still let D'Aurevilly have the last word:

"Those who see things only from a narrow point of view have imagined [dandyism] to be especially the art of dress, a bold and felicitous dictatorship in the matter of clothes and exterior elegance. That it most certainly is, but much more besides. Dandyism is a complete theory of life and its material is not its only side. It is a way of existing, made up entirely of shades, as is always the case in very old and very civilized societies, where comedy becomes so rare, and the properties hardly have the better of boredom."