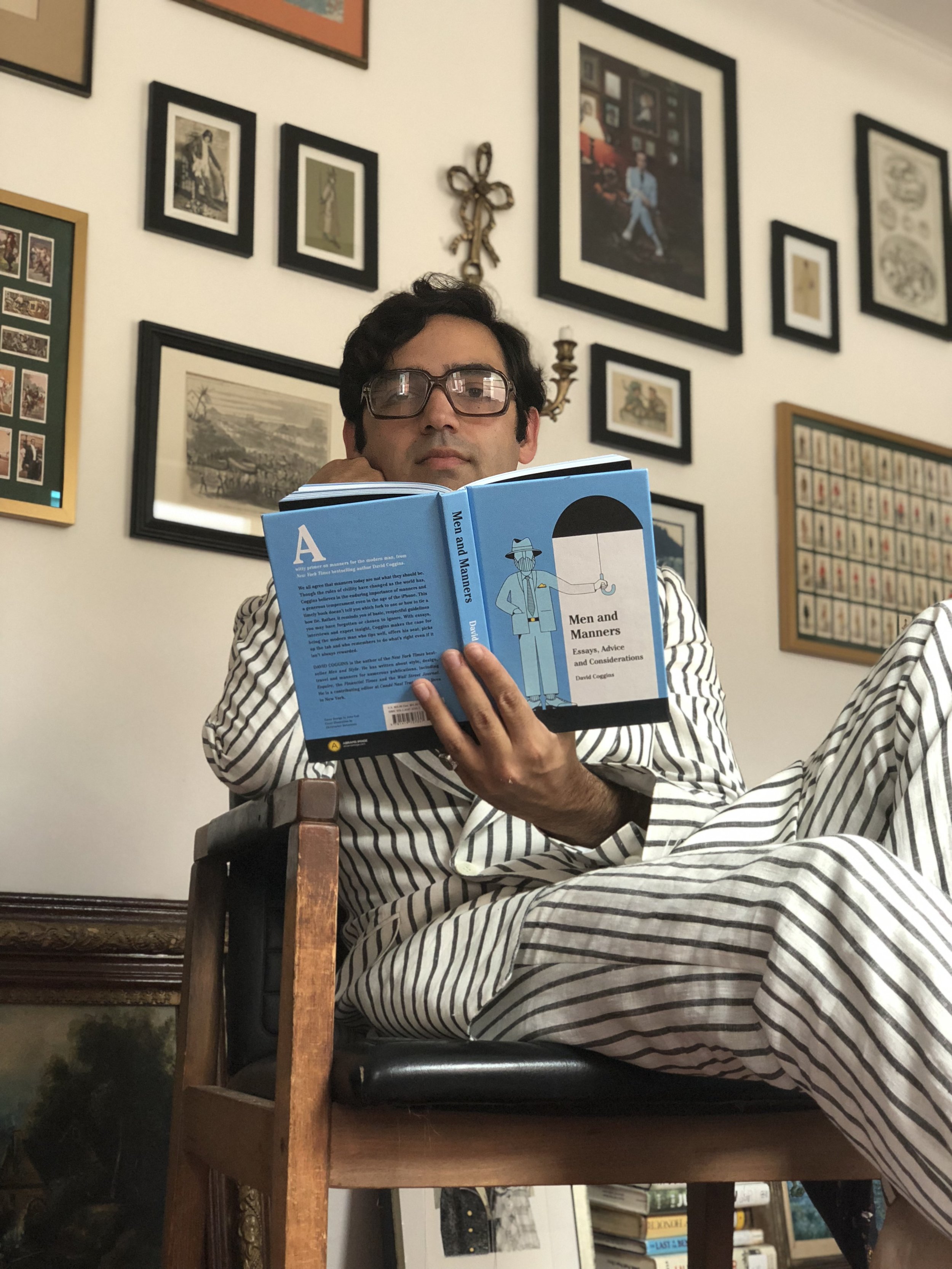

In a year in which I've published little of great consequence, it's a particular delight to have been invited by my friend David Coggins to contribute a few thoughts to his excellent book Men and Manners, (Abrams, 2018,) the follow up to his New York Times best-selling Men and Style (Abrams, 2016.) I was as shocked as you that someone would want my opinion on manners of all things, but when I learned that part of the job involved me grousing about things that annoyed me, I felt safely on my home turf again. The book is truly wonderful to read: witty, warm, and with a generosity of spirit befitting the subject. It is a book that treads lightly, never taking itself too seriously, occasionally self-deprecating, and above all patient. In fact, if I were to distill all of the lessons of this book down to one virtue, it would be patience. A few oblique references are made at the beginning of the book to the tense and angry political climate post-2016, and a subtext that occurred to me while throughout was: "above all else, keep your cool" - Coggins counsels (indeed channels,) the almost zen-like magnanimity of our last president.

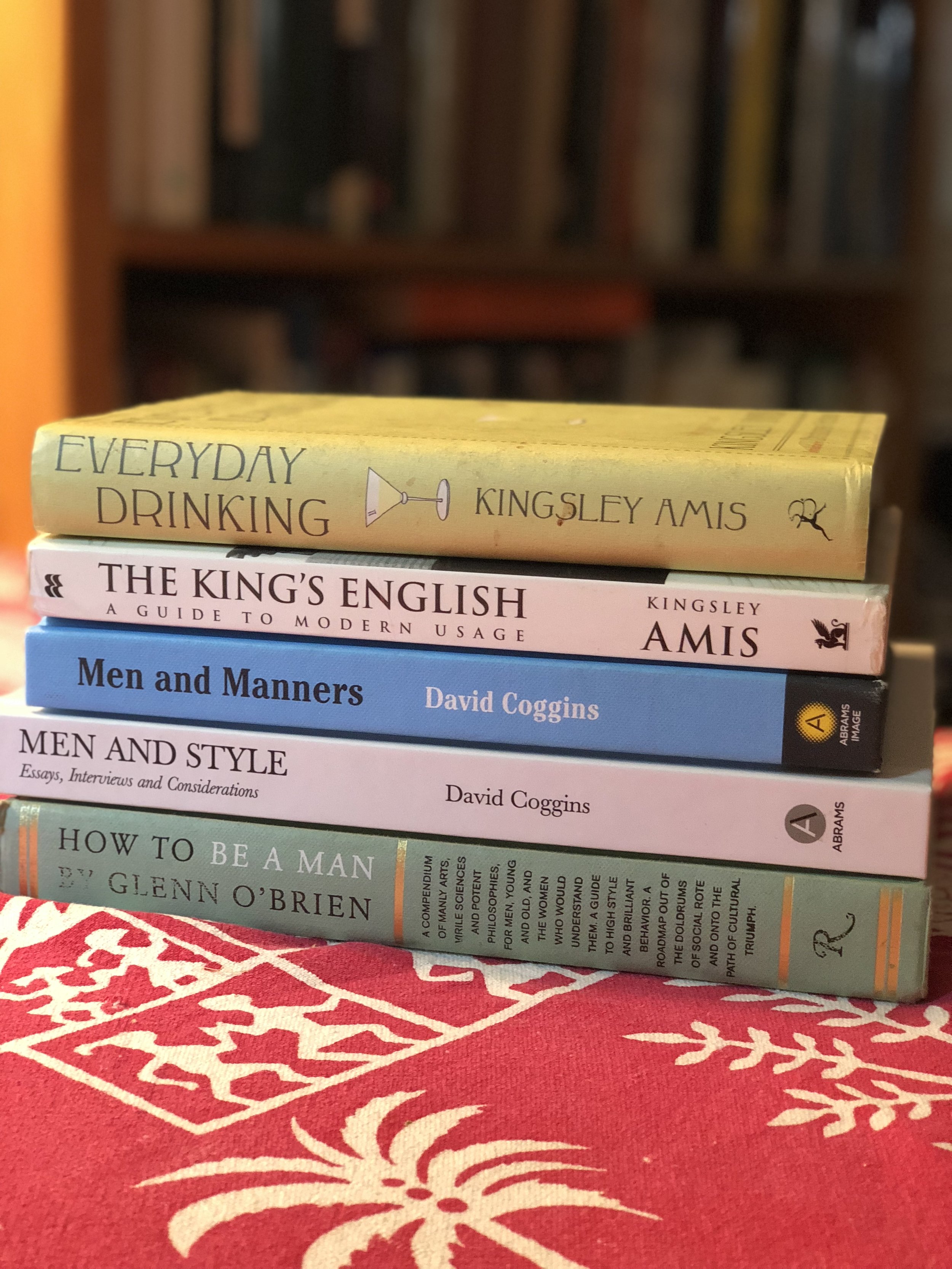

Books of advice are tricky things, and notoriously difficult to shelve at a bookstore (this canny and semi-ironical gem certainly doesn't seem at home in the high-stakes con-artist-filled self-help section.) My two favorite advice books are both by the same author on different subjects: Kingsley Amis's Everyday Drinking (the compiled version with the Christopher Hitchens introduction,) and The Kings' English, Amis's hilarious and savage defense of proper English usage. This book is similar in style to those (though less obviously curmudgeonly,) and even name-checks the first volume mentioned. Aside from a taste for nice clothes, good booze, and Kingsley Amis, Coggins and I also share two mentor/friends in writers Gay Talese and the late Glenn O'Brien. In fact, both of Coggins's books are most like O'Brien's How to be a Man in feeling and intent. Coggins and I also both have close relationships with our fathers, and I was delighted to share a piece of my father's wisdom for the book, and then give him a copy of it for Father's day. Unfortunately, I forgot to include my dad's Bartleby-like motto "you don't have to do anything."

Adams, Coggins, Callahan

That the book is such a delight to read is - apart from its excellent style - due to Coggins's easy flexibility as a guide through the pitfalls of modern living; he is confident in his opinions without any pretense of infallibility, unafraid to tell you what he prefers, but - despite the magnificent beard - reluctant to cast himself as a Moses of etiquette. There are a few particularly excellent rules and tips laid down here and there that Coggins insists you shouldn't compromise on and that double as affirmations of the author's good taste. He says "if something will fit when you lose weight then it doesn't fit." This is what I've always referred to disparagingly in the bespoke business as "aspirational sizing," and it is when a man appears most pathetic to his tailor. Coggins has a nearly perfect Martini preference - very cold gin, don't be afraid of the vermouth, stirred, served with a lemon peel twist - that I would only tweak by swapping the twist for a cocktail onion, thereby turning it into a potently bittersweet Gibson. Coggins also recommends the Giotto frescos in Santa Croce, at which point in reading I nearly jumped for joy at the discovery that I wasn't the only person at Pitti Uomo spending quality time off-campus, as it were. Perhaps Coggins's greatest advice is "nobody is your 'bro.'"

The Pentateuch

The closest thing I have to a criticism of the book is that it knows its audience too well, and plays with them very nicely indeed (probably a good and natural thing for a book about manners.) There is no direct discussion about how a good-mannered person deals with people with truly appalling manners, for example. The recommendations are also often New York-centric - Manhattan, specifically - which is something I don't think I would have even noticed until I moved away from the city - so blinkered are even the best-travelled New York cosmopolitans to the possibility of a serious life elsewhere. A section on travel assumes that journeys will be undertaken via airplane and counsels the manners-minded traveller to find ways to make the best of it - my hopes for a full-throated endorsement of a return to rail travel until air travel becomes less of a hellish ordeal went unsatisfied, but that's a personal problem, and Coggins was certainly wise to write for the flying majority. Coggins also nimbly avoids several contemporary cultural minefields (and who can blame him?) by mainly ignoring them: there is a sort of unspoken understanding, gleaned from the various mentions of relationships with women that the man in the title is probably a straight man, and not only that but that he is an educated, urbane, and sophisticated man of some means who travels internationally, stays at hotels, eats at restaurants often, and goes to parties where wine will be drunk. One is somewhat depressed by the almost certain knowledge that the brazen philistines of the world - the ones who have lots of 'bros,' - are exactly the least likely to read a book about things like tipping and grooming and not cutting people off in traffic or spitting on the floor or sending unasked-for anatomical photos to ladies. I often wondered while reading it what the 13 year-old boys I mentor in East Baltimore public schools would make of some of the advice: hold the door for people, check. Don't text during dinner, got it. But own your own tuxedo and hang art on your walls? Is that perhaps too bourgeois and patronizing a concern? The exclusive domain of we privileged and patrician few? Or is it part of a worthy, cultured life for men of any class, color, and creed to aspire to? I may have to bring the book in and ask the kids what they think.

Where the book truly excels is in its treatment of distinctly contemporary social phenomenon for which mores and standards are still evolving: texting, social media posting, online dating. The advice it gives for these is brilliant, always thoughtful, based on principles of fair play, and - most importantly - never arbitrary. The book is also sensitive to and aware of many less-noted social subtleties - Coggins is nothing if not an expert observer of human interaction. The section on how to break up with someone well would have been a blessing to a (not-that-much-)younger me. I was glad to see that my father's advice about knowing when to quit the field and keep the peace in an argument is echoed and elaborated upon in one of Coggins's own sections, which reminded me of one of my favorite song titles: "Why Are You Being So Reasonable Now?" by the Wedding Present. I'm not sure what Coggins is working on next - could he possibly have more sage advice to give? Whatever it is it is sure to be a pleasure to read and a treat for those of us who idly aspire to sophistication.