When asked to list my favorite authors or books, I’m sometimes criticized for not including enough (or indeed any,) women. When I say that it’s because I like funny books, said critics can get pretty angry.

Of course I don't mean that women aren't funny - of course they are (or rather, can be, just as with men,) but a few unfortunate historical factors come together in a kind of Venn diagram for why the shelf of great female humorists is lamentably small. First, there aren’t that many funny authors of any sex - I think humorists are the unsung heroes of literature, almost always written off by critics as unserious and therefore not literary. Second, for most of history the proportion of male to female authors of any kind has been ludicrously unbalanced. Third, a sense of humor is just one of the many qualities of character which has for a very long time been roundly discouraged in women but encouraged in men. I fear generations of readers have suffered an unknowable misfortune in the many funny books which went unwritten by women.

But of course there are funny women authors: Nancy Mitford, Flannery O’Conner and Jane Austen spring immediately to mind. Unfortunately they’re few and far between. This is why I was so happy when someone recommended Betty MacDonald to me. I’d never heard of MacDonald, but she was an incredibly popular author in the 1940’s and 1950’s for her comical memoirs and children’s books, selling millions of copies and gaining national fame (as well as a dedicated fan-base in the UK.)

One the best things about MacDonald’s memoirs is that they are explicitly about the life of women of her time and indeed what might be considered uniquely female experiences, but the humor is confidently universal, never boxing itself in by struggling to seem self-consciously “feminine” in style or target or intended audience. This seems to me a very rare and bold and wonderful thing for a female author to do in the middle of the last century. Or any time, probably.

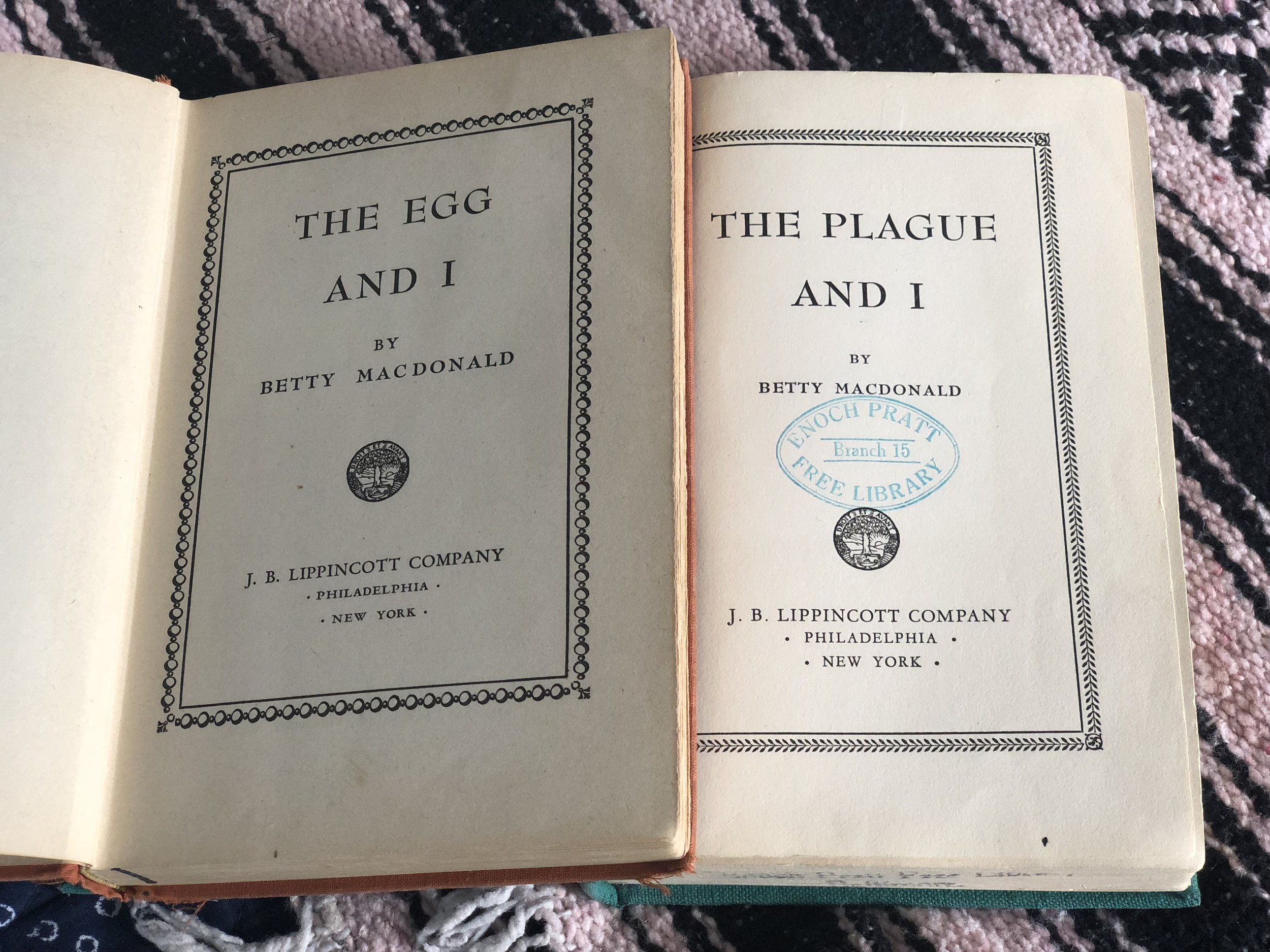

Her first and most famous memoir, “The Egg and I,” tells the story of young Betty, newly married, following her mother’s advice for marriage and agreeing to support the career and wishes of her husband, whatever they may be. Unfortunately for Betty, during their honeymoon her new husband Bob announces that what he’s really always wanted to do is start an egg farm in the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. Knowing nothing about farming, egg or otherwise, but desiring a happy marriage at any cost, Betty agrees and the two take up residence in a small leaky cabin somewhere in the thickly-wooded mountains of Washington State.

What ensues is Betty’s deep-end plunge into the worlds of crop rotation, animal husbandry, bear defense, and foraging added on to the traditional wifely duties of cooking, cleaning, and birthing and raising children, all while her husband, increasingly invested body and soul into the raising of their little egg empire, grows more and more estranged from her life and needs.

Like Jerome K. Jerome, MacDonald, while always unimpeachably funny, occasionally digs into her toolbox to really impress the audience and set a scene with vivid description:

I watched mornings turn pale green, then saffron, then orange, then flame colored while the sky glittered with stars and a sliver of a golden moon hung quietly. I watched a blazing sun vault over a mountain and leave such a path of glory behind that the windows of mountain homes like ours glowed blood red until dark and even the darkness was tinged and wore a cloak of purple instead of the customary deep blue. Every window of our house framed a vista so magnificent that our ruffled curtains were as inappropriate frames as tatted edges on a Van Gogh. In every direction, wherever we went we came to the blue softly curving Sound with its misty horizons, slow passing freighters and fat waddling ferries. The only ugliness we saw was the devastation left by the logging companies. Whole mountains left naked and embarrassed, their every scar visible for miles. Lovely mountain lakes turned into plain ponds beside a dusty road, their crystal water muddy brown with slashing and rubbish.

I loved the flat pale blue winter sky that followed a frosty night. I loved the early frosty mornings when the roofs of the chicken houses and the woodshed glowed phosphorescently and the smoke of Bob’s pipe trailed along behind him and the windows of the house beamed at me from under their eaves and Stove’s smoke spiraled thinly against the black hills.

Another specific talent of MacDonald's are her sometimes mouth-watering accounts of food to rival M.F.K. Fisher:

I accepted as ordinary fare pheasant, quail, duck, cracked crab, venison, butter clams, oyster, brook trout, salmon, fried chicken and mushrooms. At first Bob and I gorged ourselves and I wrote letters home that sounded like pages ripped from a gourmand’s diary, but there was so much of everything and it was so inexpensive and so easy to get that it was inevitable that we should expect to eat like kings. Chinese pheasant was so plentiful that Bob would take his gun, saunter down the road toward a neighbor’s grain field and shoot two… and come sauntering home again.

But best of all, in the great tradition of humorists like Mark Twain, MacDonald’s writing shines in the dialogue and dialects of her characters, no more so than in the mouths of her neighbors, the ever-cussing Mrs. Kettle and her lazy lisping husband Paw Kettle:

Mrs. Kettle began most of her sentences with Jeeeeeesus Key-rist and had a stock disposal for everything of which she did not approve, or any nicety of life which she did not possess. “Ah she’s so high and mighty with her ‘lectricity,” Mrs. Kettle sneered. “She don’t bother me none - I just told her to take her old vacuum cleaner and stuff it.” Only Mrs. Kettle described in exact detail how this feat was to be accomplished. As Mrs. Kettle talked, telling me of her family and children, she referred frequently to someone called “Tits.” Tits’ baby, Tits’ husband, Tits’ farm, Tits’ fancywork. They were important to Mrs. Kettle and I was glad therefore when a car drove up and Tits herself appeared. She was a full-breasted young woman and, even though Mrs. Kettle had already explained that the name Tits was short for sister, I found it impossible to hear the name without flinching. Tits was a Kettle daughter and she had a six-month-old son whose name I never learned as she referred to him always as “You little bugger.” Tits fed this baby pickles, beer, sowbelly and cabbage and the baby ungratefully retaliated with “fits.” “He had six fits yesterday,” Tits told her mother as she fed the baby hot cinnamon roll dipped in coffee…

…Paw alone retained his savoir faire. He came clumping up onto the back porch exuding barnyard odors and good will, and after a few hearty stamps to loosen any loosely caked mud or manure he settled himself full length on the shiny leather couch. Mother said to Mrs. Kettle, “Do you mind if I smoke?” “Not at all, not at ALL,” boomed Paw. “Thmoke A WHOLE CARTOON if you have a mind to. Anyone want a THIGAR?” and he laughed uproariously as he proffered a much-chewed cigar end.”

The other MacDonald book I read was “The Plague and I,” one of the sequels to the first book. Betty is now divorced, although this is never explicitly dealt with in the book (it was still something of a taboo subject in the 1940’s,) and she is raising her children with the help of her mother and sisters when she is diagnosed with tuberculosis and sent to live in a sanitarium.

It’s a credit to MacDonald’s brilliance as a storyteller that she can chronicle a year of near-inaction in the rarified and morbid setting of a TB clinic with so much wit and humor. Again, she reveals to the reader a world most people don’t experience firsthand - then it was egg farming, this time it’s a very possibly terminal illness - and a way of living and type of experience that would have been unique to women at the time: the nearly thankless realm of a farmer's wife in the first book, the enforced ennui of a women's hospital ward in the second. In both instances, MacDonald is thrust into situations that are not of her choosing, whether it's by wanting to please her selfish husband or by being laid low by illness and then feeling a pressure on all sides to get well at all costs.

MacDonald’s descriptions of hospital life and the oppressively dull routines forced on her and her fellow consumptives are funny, depicting a place where anything joyful is forbidden in the name of resting the lungs and the nurses’ directive seems to be to to remind the girls how lucky they are to be convalescing in such a wonderful institution. She chronicles each day’s minutiae with wit:

Sunday morning at five o’clock I heard the sweet-faced, gentle Catholic Fathers going softly from room to room on the promenade, blessing their people… and even though I am an Episcopalian I often wished that one of them would stop at my bed. …The other ministers came too, but only on occasion and usually during visiting hours. No doubt their intent was good but to attempt to make contact with God during visiting hours was as futile as trying to pray at a cocktail party.

Again, MacDonald is at her best with her characters and dialogue, in this case a somewhat fluid cast of nurses, doctors, and roommates who come, go, and reappear at various stages of her treatment. Most notable among these are Eileen, the oversexed rule-breaker with red fingernails, Minna, the tattling southern belle and darling of the ward nurses, and the unforgettable Kimi, an unusually tall Japanese girl with a dry and morbid wit coupled with inborn grace and poise:

When the nurse made her rounds that evening Minna said “You know that ole list didn’t have a bed lamp on it and it’s so dahk and lonely heah in the cohnah. Ah wrote mah Sweetie-Pie to bring me a bed lamp but it won’t be heah until next visitin’ day. Ah suah am lonely.” The Charge Nurse brought her a bed lamp, which had probably belonged, Kimi gently reminded her, to some patient who had died. At the time Eileen didn’t have a bed lamp either and she was furious. As the Charge Nurse finished attaching Minna’s lamp, Eileen said “Well, Jesus, honey, it’s dark ovah heah too,” but all she got was a cold look.

Minna had only one visitor…”Sweetie-Pie,” her adoring husband. Sweetie-Pie was about fifty years old, bald, fat, and doughy-faced, but he brought Minna flowers and candy and bath powder and fruit and bath salts and jewelry and perfume and bed jackets. She always referred to him as though he were a cross between Cary Grant and Noel Coward and said often, “Ah just don’ know how I was lucky enough to get that big ole handsome husband of mine.”…

…Eileen had said, “You can stop right after the ‘big old,’” and strangely enough Minna began to cry…

…After [Sweetie-Pie] had gone, Minna sat up and ate every crumb of her supper including two helpings of the main dish. Kimi looked over at her, wearing a new pink angora bed jacket and happily eating soup, while the mournful steps of the deflated Sweetie-Pie dragged along the corridor, then said softly, “With what a vast feeling of relief he will close the lid on your coffin.” I choked on my soup and Eileen shouted with glee. Minna said only, “Next week he’s bringin’ me a pink hood to match this jacket.”